Philosopher Carlos Montemayor and cognitive scientist Harry Haroutioun Haladjian synthesize a very large amount of philosophical and psychological research in this short book. They address several philosophical issues over the course of its five chapters, bringing to bear several branches of psychological enquiry. They consider results from not only those branches of psychology explicitly concerned with the investigation of attention and consciousness, but also those concerned with dreaming, temporal awareness, the purportedly illusory experience of conscious will, and the purportedly selfless experience of 'flow'. There is even one point at which they incorporate ideas that they attribute to Proust and to Tolstoy. Their objective in bringing this impressively broad range of material together is to establish the extent to which the three eponymous phenomena are dissociable.

Previous attempts to probe the relationship between those phenomena have suffered from something that is analogous to Chisholm's Problem of the Criterion. To see this, consider Irvin Mack and Arien Rock's work on Inattentional Blindness (1998). Mack and Rock found that several of their experimental participants showed no conscious awareness of certain visual stimuli presented in a context in which the participants' attention was directed at something else. When their attention was directed to a pair of crossed lines, for example, Mack and Rock's participants often showed no awareness of a word that was briefly flashed up in the centre of their visual field. This effect was found for some stimuli but not for others. When the flashed-up word was a correctly spelled version of the participant's own first name, that participant typically did report seeing it. When the participant's name was spelled incorrectly -- by having its first vowel switched for another -- it very often went unnoticed.

In arguing from these results to a claim about the relationship between attention and consciousness one faces a difficulty (similar to Chisholm's Problem). According to one theory of that relationship, a person is not conscious of some thing unless she has given it her attention (Prinz, 2011; Cohen et al., 2012). According to a rival theory, there are some stimuli that can figure in a person's consciousness, even when no attention is paid to them (Hardcastle, 1997; Li et al., 2002). The dispute between these theories is supposed to be a substantive matter rather than a point of terminology. We need empirical evidence to settle it. Defenders of the first theory will take the evidence given by Mack and Rock to vindicate their position, interpreting those results as showing that stimuli such as names come into our consciousness only because they are stimuli to which our attention is involuntarily attracted. Defenders of the rival theory can just as easily take Mack and Rock's results to be a vindication of their position despite the fact that this position is incompatible with the first. These latter theorists will interpret Mack and Rock's results as showing that stimuli such as names do come into our consciousness, even when our attention is directed elsewhere.

Results such as those from Mack and Rock are therefore unable to adjudicate between these two different theories of the attention/consciousness relation until we have given some criterion for determining whether or not attention has been paid to a stimulus and some criterion for determining whether or not that stimulus has featured in consciousness. The Chisholmish difficulty is to settle on what these criteria should be without begging the question of how consciousness and attention are related. (Notice that we cannot address this problem by taking first person reportability as our criterion for consciousness since a stimulus's unavailability for first-person report might be explained by a lack of attention to it, whether or not that lack of attention results in a lack of consciousness.) This need to find non-question-begging criteria for attention and for consciousness does not create an insuperable difficulty, but it does require careful negotiation (see Jennings, 2015, for a recent attempt to negotiate it). The failure to negotiate this difficulty has hindered several of the attempts to probe the relationship between attention and consciousness empirically.

Montemayor and Haladjian hope to avoid this sort of difficulty altogether. Their tactic is to shift away from considering particular contexts in which attention and consciousness might be found to come apart. Instead they focus (although by no means exclusively) on the ways in which attention and consciousness might have evolved. "These considerations about the evolution of attention and consciousness and how they are related are", the authors say, "central to the contribution we hope to make with this book." (p. 18). That contribution is advertised as being a decisive one. It is suggested that once evolutionary considerations are introduced "immediate progress in this debate is achievable" (p. 6).

The direction of that progress becomes clear in the fifth chapter when these evolutionary considerations are given centre stage. There the authors claim that:

the scientific findings about attention and basic considerations about the evolution of different types of attention demonstrate that consciousness and attention must be dissociated regardless of which definition of these terms one uses. . . . Because of this characteristic, we can now present a principled and neutral way to settle disputes concerning this relationship, without falling into debates about the meaning of consciousness or attention. A decisive conclusion of this approach is that consciousness cannot be identical to attention. (p. 177)

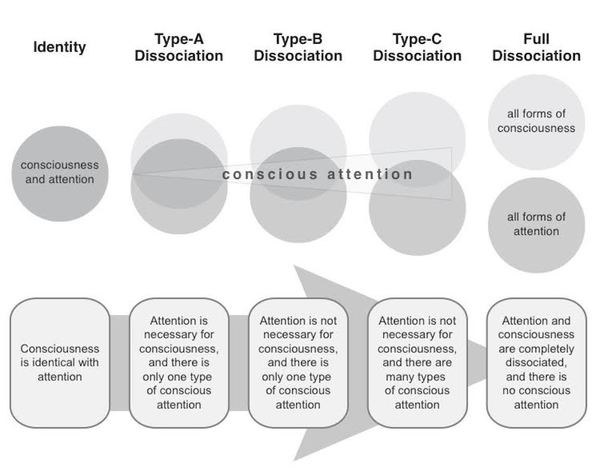

As the last sentence of this quotation indicates, the claim that Montemayor and Haladjian take themselves to be opposing in this part of their discussion is the claim that attention and consciousness are identical. (This 'identity view' is named as their target on pp. 177, 179, 185, 192, 201, and 210.) There are several different ways in which two phenomena might fail to be identical, and so there are several ways in which an identity view might be opposed. Lack of identity might involve a distinctness as large as that between shoes and ships or as small as that between a cat and its smile. Montemayor and Haladjian attempt to clarify the possible degrees of dissociation between consciousness and attention in the first part of their discussion using the diagram below to represent a spectrum of possible positions.

Although it provides a useful reminder that there are several positions one might take, this spectrum is a somewhat unnatural way in which to represent the space of available views, even by Montemayor and Haladjian's own lights. Its unnaturalness can be seen when we compare the relationships that are depicted in this diagram's top half with the glosses that are given in its bottom half (and in the text, p. 5).

The top half of the diagram shows a light grey circle, representing 'all forms of consciousness', and a dark grey circle, representing 'all forms of attention'. In the part of the diagram representing 'Type-A Dissociation', these circles are largely overlapping, with neither one of them falling entirely within the other. The prose gloss says that this 'Type-A' view is committed to claiming that 'Attention is necessary for consciousness'. That would imply that attention is involved in every instance of consciousness and so would imply that the relative complement of attention in consciousness must be empty. But this is not what the diagram depicts. Similarly, one might have thought that any form of attention that is also a form of consciousness is, ipso facto, a form of conscious attention. A greater area of intersection between the 'forms of attention' circle and the 'forms of consciousness' circle would then indicate that there are more ways in which conscious attention is possible. But again the prose gloss indicates that some other interpretation is needed. In a type C dissociation, where the intersection of the circles is shown as being relatively small, the prose gloss tells us there are "many types of conscious attention". In the dissociations of types A and B, where the intersection is shown as being relatively large, the positions are glossed as saying that "there is only one type of conscious attention".

These considerations suggest that what we have here are, in fact, two distinct issues. One, represented by the diagram's circles, is a question about whether attention is necessary for all, some, or no forms of consciousness. The other, represented by the wedge shape that has been superimposed onto those circles, is a question about the number of types of 'conscious attention'. These issues are distinct (at least until some principle has been specified by which instances of 'conscious attention' are to be divided into types). The positions that one might take on those issues need not be aligned into a one-dimensional spectrum.

The problem here is not merely that an unfortunate diagram has been used to illustrate some thinking that can nonetheless be clearly understood. The diagram is an indication of one point at which confusion has not been averted. When Montemayor and Haladjian themselves refer back to the spectrum of positions that is indicated by it, they need to allow some latitude on what those positions are. We are told that "If it is true that consciousness has no cognitive function, then the type of dissociation between consciousness and attention must be either the most severe (full dissociation of independence), or very severe with very few cases of conscious attention (Type-C CAD)." ( p. 179). Notice, however, that their diagram had defined a type-C view as one in which, rather than there being "very few cases of conscious attention", there are "many types of conscious attention". Here the authors show their willingness to treat their own taxonomy as imprecise.

Such imprecision is damaging because Montemayor and Haladjian also suggest that the introduction of this taxonomy will be one of their book's major contributions. They claim that this "will help to reshape the debate on the relationship between consciousness and attention" and that "significant clarity emerges when debates are reinterpreted in this way", with the result that "our spectrum of dissociation approach will constrain, both empirically and theoretically, current views on consciousness and attention and, we hope, produce more meaningful exchanges with respect to their relationship" (p. 21).

One of the virtues that they claim for this taxonomy is that all tenable positions are assigned to a distinct place in it, including some that had not hitherto been visible:

the spectrum of dissociation that we develop presents a much more finely grained set of possibilities, more intricate than any extant view is capable of capturing. . . . it shows . . . that the number of options is much larger than we had previously thought. (p. 22)

A fine-grained taxonomy might indeed be a useful thing to have, especially if consensus could be reached as to the terms in which that taxonomy was framed, but there is room to doubt whether 'Type-A', 'Type-B', and 'Type-C' dissociation are the terms that we need. One position in these debates that has previously been thought tenable is that taken by Wilhelm Wundt in the first chapter of his Introduction to Psychology. Wundt held, like some of the phenomenologists who followed him, that one is conscious of many things, most of which fall into the inchoate background of one's experience. Some subset of those things is experienced clearly and is thereby brought into the foreground of consciousness. This conscious foregrounding is what Wundt identified as attention (Wundt, 1912, p. 16).

Since it is a view according to which our consciousness includes an unattended background, Wundt's is not a view according to which attention to a thing is necessary for consciousness of it. Its commitments therefore correspond to those that Montemayor and Haladjian specify for Type B or Type C dissociations. But Wundt takes the relationship between attention and consciousness to be a very intimate one: attention, on his view, is one particular kind of consciousness. It might even be that consciousness has its figure/ground structure essentially, so that there is something to which one is attending whenever one is conscious. Wundt's view that attention is the foreground of consciousness and the view that consciousness is itself a consequence of attention do not belong at different points on a single spectrum of views at all. The linear spectrum that Montemayor and Haladjian propose distorts the logical space around this issue. It thereby prevents us from getting a clear view of what has, traditionally, been one of central debates concerning it.

This point is not merely historical. Montemayor and Haladjian's taxonomy needs to be distorted in order to make room for the claims to which their own arguments commit them. We quoted above from the discussion in which the authors consider the possibility that 'consciousness has no evolutionary function'. Immediately following that quotation, they go on to say:

Alternatively, if consciousness has a specific evolutionary function, and theorists seek to provide an identity view or even a mild dissociation view (Type-A CAD), then they will face the challenge of specifying how consciousness as a cognitive function coevolved with attention, which can then be defined in terms of specific types of cognitive functions, such as voluntary, object-based, feature-based, or spatial attention. Given our current theoretical and empirical understanding, we suspect that this latter possibility will not materialize. (p. 179)

When we attempt to understand the argument that is indicated here, it clouds the issue to consult the taxonomy that the authors have provided. The argument of this passage looks to be an argument against 'an identity view or even a mild dissociation view (Type-A CAD)'. The authors' taxonomy indicates that these are the only two views according to which attention is necessary for consciousness. They therefore seem to be arguing for a position that rejects that commitment. And yet this commitment is one that they explicitly endorse: "it is likely that some form of crossmodal attention is necessary for consciousness." (p. 210, cp. p. 23). Here Montemayor and Haladjian's conceptualization of the logical space in which they are operating proves to be unhelpful, even for the articulation of their own view.

Return now to the question of whether evolutionary considerations enable Montemayor and Haladjian to establish that view via a route that avoids the Chisholm-like problem with which we began. They claim that the introduction of these considerations enables them to dodge the difficult business of defining terms. They write that:

One crucial advantage of an evolutionary approach for understanding the relationship between attention and consciousness is that it demonstrates that they must be dissociated regardless of how one defines them among the viable options currently available within the debate. (p. 204, emphasis original)

A few pages later Montemayor and Haladjian are explicit about what they take the constraints on viable definition to be. They state their conclusion -- that "Consciousness cannot be identical with attention" -- and then go on to claim that:

Unlike any other extant view, our conclusions hold regardless of how the terms 'consciousness' and 'attention' are defined -- as long as we agree that basic attention is the selective processing of information by low-level sensory mechanisms and that consciousness is the phenomenal experience that can be influenced by these processes. (p. 209)

Since Montemayor and Haladjian hold that attention is necessary for consciousness (and say so on this page) the dissociation being claimed here is only one way. Their conclusion that 'consciousness cannot be identical with attention' is therefore no stronger than the claim that "low-level sensory mechanisms" can engage in "the selective processing of information" without any phenomenal experience taking place.

I do not think that anybody would resist this conclusion. The work that Montemayor and Haladjian repeatedly cite as representative of the 'identity view' that they take themselves to be refuting is Jesse Prinz's The Conscious Brain. But Prinz would certainly not deny that "low-level sensory mechanisms" can engage in the selective processing of information in the absence of phenomenal experience. He comes close to asserting that very claim in the work that Montemayor and Haladjian cite when he says that "Features that are represented only at the low-level cannot be experienced" (Prinz 2012, p. 71).

Prinz would be happy to accept that low-level unconscious representations can be processed selectively but would not use 'attention' as the name for such processing. When he claims that there is something like an identity relation between consciousness and attention, he is not using the word 'attention' in a way that includes "the selective processing of information by low-level sensory mechanisms". (He is using 'attention' to denote the process of transmitting information to working memory, as Montemayor and Haladjian themselves note (p. 113).) In order to maintain that their conclusions hold "regardless of how one defines ['attention' and 'consciousness'] among the viable options currently available within the debate", the authors must therefore claim that Prinz's definition of 'attention' is not "among the viable options currently available within the debate". A case might perhaps be made for this claim, but the making of it would return us to the Chisholm-ism problem of determining which definitions for our terms would be question-begging.

The contribution made by this informative book is therefore something less than the "decisive conclusion" advertised by its authors. Philosophers should nonetheless be grateful to them for displaying the range and complexity of the issues and findings that should constrain our theorizing about these aspects of the mind.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks to Carlos Montemayor, for providing a copy of the diagram reproduced above.

REFERENCES

Cohen, M. A., Cavanagh, P., Chun, M. M., and Nakayama, K. (2012). The attentional requirements of consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Science , 16 (8), 411-417.

Hardcastle, V. G. (1997). Attention vs. Consciousness: A distinction with a difference. Cognitive Studies: Bulletin of the Japanese Cognitive Science Society , IV, 56-66.

Jennings, C. D. (2015). Consciousness without attention. Journal of the American Philosophical Association , 1 (2), 276-295.

Li, F.-F., Van Rullen, R., Koch, C., and Perona, P. (2002). Natural Scene Categorization in the Near Absence of Attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. , 99, 9596-9601.

Mack, A., and Rock, I. (1998). Inattentional Blindness. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Prinz, J. J. (2011). Is Attention Necessary and Sufficient for Consciousness. In C. Mole, D. Smithies, and W. Wu, Attention: Philosophical and Psychological Essays (pp. 174-203). New York: Oxford University Press.

Prinz, J. J. (2012). The Conscious Brain. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wundt, W. (1912). An Introduction to Psychology. (R. Pintner, Trans.) London: George Allen and Unwin.