The telling title of this excellent book takes us right away to the good stuff, beyond the letter of the law, beyond duty, and to the spirit of Kantian ethics. Duty-talk tracks exacting demands, which are surely interesting—but duty-talk also, with Kant, leads us to formal requirements, to the law, and so has a way of moving us away from whatever it is that animates Kantian ethics, from its spirit, from what moves Kant and Kantians to want to follow the law in the first place. Thomas Hill is at home with the spirit of Kantian ethics, and we are all lucky this is so.

Hill’s book collects essays written during the last decade, for different purposes and audiences, all held together by Hill’s commitment to seeing the spirit of Kantian moral ideals at work in real life. The earliest was published in 2013, forty years after Hill’s essential 1973 Monist essay, “Servility and Self-Respect.” We are lucky that Hill has been thinking and writing so well for so long. And we are lucky that he addresses so many: the essays here were written for educators, lawyers, moral philosophers, readers of the Cambridge Companion to Life and Death, APA members—there’s a great Presidential Address here—as well as, of course, for Kant specialists.

We are also lucky Hill is writing now. It is a strange time to be a Kantian. It is a strange time to be a person of any kind, to be sure. But for Kantians, for those of us teaching Kantian practical theory, there are special hurdles. The language of dignity, given daily indignities and the din of indignation, of respect for humanity when humanity seems to have destroyed its own future, of agency when learned helplessness feels like the order of the day—this language can fail to find purchase with our students and other audiences. We, and they, face short supplies of awe at the starry skies, and of appreciation for the math and science that map them, and equally short supplies of awe at the moral law within, at our own capacity to transcend personal interests and to see things universally. But reading Hill, we can be reminded of the ways many of us are still at it, many of the ways we can still get better, can still work to attend, appreciate, respect, and nurture humanity even in, in the volume’s actual final words, “our messy and often cruel world.”

The nine essays in Part I, “Kant and Kantian Perspectives,” take up exegetical issues and scholarly debates about reading the Groundwork as a whole, about imperfect duties to oneself, about autonomy, the rational basis of human dignity, about the kingdom of ends, ideal or utopian theory, and about constructivism. My descriptions here borrow quite exactly from the essay titles. They are wonderful, rich essays, of interest to anyone already engaged and/or eager to get up to speed on these debates.

The eight essays in Part II, “Practical Ethics,” take up puzzles posed by rich and often very emotionally difficult and complex particulars: how to grapple with the ethics of tragic, or morally repugnant, choices (like Sophie’s, or those faced by people caught up in war or conditions of profound scarcity); how to think properly about kinds of philanthropic giving; what to think about suicide, including assisted suicide; about the Kantian implications of Kimberley Brownlee’s work on conscience and civil disobedience; about Rawls, political stability, and self-respect; about civic virtue and moral education; and finally, powerfully, about an ideal of appreciation (and its relationships with respect and beneficence and disability).

For me, the most exciting part of Hill’s work lies here. Yes, for Hill (and to quote Hill himself),

A moral life is understood as a life of rational self-governance based on respect for humanity in each person and solidarity with all persons. Caring about morality is, in the language of the day, partly a matter of respecting 'who one is.' Human dignity is a universal and inalienable moral status based on these ideas. (2)

Yes, yes. But what if our considerations of moral life thus described take seriously, for instance, that “nature or circumstance may cause some people to grow up abnormally grumpy, fearful, or flighty” (251)? What if, to turn to appreciation, we took the following to heart?

The ideal of appreciation I take to be an openness to acknowledge, take in, and attend to the myriad good things about particular persons and the good things that they may experience in their lives. [. . .] The good things that I have in mind include not only their traits of character and personality but also the things that they can experience as valuable and worth attending to, whether this is deep or trivial, moving or funny, classy or just fun. (286)

For Hill, appreciation is a form of oriented attention: “The person with appreciation has the confident attitude, belief, or faith, that there are really good things, actual and potential, in the people with whom they are closely connected and in their lives” as well as “in oneself and one’s own life” (287–8). To appreciate another, or oneself, in Hill’s sense, is to have an abiding sense of the person as a subject with a rich history, inner life, set of relationships and concerns, and capacities for joy, love, and grace—rather than as an object to be navigated or pitied, let alone used (see p289 where Hill notes that appreciation coheres with dignity). To fail to appreciate is, in an important sense, to fail to see the other. Hill again: “the primary enemies of appreciation in close relationship are familiar weaknesses and vices—indifference and insensitivity, inattention and impatience, annoyance and anger, self-absorption and laziness” (292). Hill in a footnote: “It is perhaps appropriate to note that the German word Achtung is translated as respect as well as a call for attention” (n5, 283). (I have a good friend who for a time expressed his highest praise of someone or something by exclaiming, “A is really paying attention!”). For Hill, appreciative attention is also disrupted by misplaced kindness, elitist conceit, timidity, envy, and false pride (292).

Hill investigates each of these with gentleness and subtlety. Who among us has not fallen into these holes from time to time? Hill helps us see ourselves by giving us characters, which are enormously helpful: a discussion in Chapter 17 (“Ideals of Appreciation and Expressions of Respect”), for instance, tracks the ways Distant Father, Curious Sister, Grumpy Grandad, Unexpressive Uncle, and Outgoing Auntie all manage, or fail, to relate appreciatively to a gay man and his partner.

My only criticisms of the book name missed opportunities. I wished the work on philanthropy had taken up Lucy Allais’s brilliant analysis of Kant on giving to beggars (and of what goes wrong when individual and societal/structural obligations are confused) (2015). I wished Hill’s work on disability had engaged Eva Feder Kittay’s moving and profound work on disability and the intersections of moral, social, and political theory (1999; 2019). I suppose I wish my own work both on suicide (2016) and on the lived experience of embracing Kantian moral commitments (2010) had been engaged, but one cannot have everything.

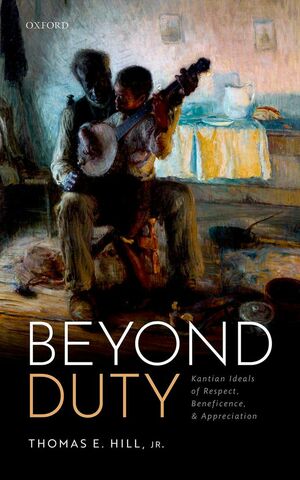

I wished the cover art, Henry Ossawa Tanner’s 1893 painting of an elderly Black man and a young Black boy, The Banjo Lesson, had been addressed and contextualized. The painting, to modern eyes, looks like a heart-warming scene of after-hours life in a plantation's slave quarters, one that surely feels off, a mystification or romanticization. Of course, it’s true that Tanner, a Black American artist working in the immediate aftermath of slavery, aimed at humanization, and at attention to the profound and hard-won successes Black Americans had achieved in sustaining intergenerational bonds and creative excellence. Yes, maybe that was the idea. But for a text (Hill’s), in a time (ours), in which deep appreciation of racialized human experience is a necessary order of business, the sentimentalization this painting threatens to perform when standing alone bears remarking.

These criticisms aside, everyone has much to learn from this collection of engaging, rich essays. Hill’s own appreciative, subtle attention to moral life is well worth ours.

REFERENCES

Lucy Allais, “What Properly Belongs to Me: Kant on Giving to Beggars,” Journal of Moral Philosophy, 12(6), 2015, 754–771.

Eva Feder Kittay, Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency (Routledge, 1999, reissued 2021 and Learning from My Daughter: The Value and Care of Disabled Minds Oxford University Press, 2019.

Jennifer Uleman, “No King and No Torture: Kant and Suicide and Law," Kantian Review 21:1, 2016, 77–100.

Jennifer Uleman, An Introduction to Kant's Moral Philosophy, Catholic University Press, 2010