Tad M. Schmaltz’s incredibly rich new book is about “the most monstrous hypothesis that could be imagined, the most absurd, the most diametrically opposed to the most evident notions of our mind”—at least, according to Pierre Bayle. The source of Bayle’s scandalization is Spinoza’s claim that God is the only substance and creatures are modifications of it, which Bayle attempts to refute in “Spinoza”, the longest entry in his widely read Dictionnaire Historique et Critique. But Schmaltz’s interest is not with some isolated philosophical beef, or even just with Spinozism’s monstrous absurdities, for Bayle diagnoses Spinoza’s chief absurdity as his (alleged) claim that finite bodies are both modes and parts of the physical world, and interprets Spinoza’s modal and mereological metaphysics in light of Cartesian and Aristotelian antecedents. An important conduit of scholastic Aristotelian metaphysics to Descartes is Francisco Suárez. So Schmaltz uses Bayle’s attack as an occasion to examine the relationship between the metaphysics of modes and mereology, especially as they bear on theories of matter. And he does so by applying his considerable expertise on Suárez, Descartes, and Spinoza.

The book’s elegant structure reflects this story. After some Aristotelian preliminaries, a section on Suárez contains a chapter on modal metaphysics and another on mereology. A section on Descartes has a chapter comparing him to Suárez and one defending his pluralism about bodies, which Bayle claims Spinoza inherits. And a section on Spinoza has a chapter comparing his metaphysics to Descartes’s, and one explicating his monism. The book is full of masterful scholarship and interpretation on a wide variety of topics, but I’ll focus just on one central thread: Schmaltz’s defense of the notion of modal parts on Spinoza’s behalf, since Bayle’s argument against Spinoza is, in large part, a dismissal of the coherence of this concept. I’ll start with a little background on the metaphysics of modes and of extended parts, as Schmaltz traces them from Suárez through Spinoza.

According to scholastic philosophers, a res (‘thing’) is what exists, in some full, proper, or basic sense. The clearest examples of res are individual substances, but most philosophers thought that so-called ‘real accidents’ are also res. Many philosophers acknowledged that there is further apparent metaphysical structure—structure that is not a matter of which res exist. For example, a single res seems able to exist in different ways or ‘modes’, which modi essendi are not themselves res. Shape is one example of a mode, but not all property-like things were thought to be modes, and not all modes are property-like.

Suárez, whose theory of modes was perhaps the most interesting and influential, characterized a mode as something that is “not properly a res or entitas, unless we use ‘ens’ broadly and most generally for whatever is not nothing.” Suárez closely tied his theory of modes to a theory of distinctions. As Schmaltz quotes Domingo de Soto: “Among all the philosophers before Scotus, there were only two distinctions: a distinction of reason and a real distinction” (41). A real distinction holds between one res and another. A distinction of reason does not hold at all ex natura rei, or in the nature of things. To get further metaphysical structure to a res without proliferating res, you need a distinction that holds ex natura rei but not between res. As Schmaltz details, Suárez draws on innovations in Scotus and Fonseca to develop an intermediate modal distinction, which holds ex natura rei, not between two res, but between a res and its mode or between two modes of one res.

That’s the picture. But we’d like to hear more about this special kind of entity that a mode has. And we’d like to know how, precisely, a distinction can be in the nature of things without distinguishing between things.

As a start on that, let’s look at a more familiar theory of modes and theory of distinctions: Descartes’s, which Schmaltz traces to Suárez. Descartes contrasts the being of a mode not with the being of a res but with the being of a substance. He defines a substance as a thing that depends on nothing else for its existence (CSM I 210), and a mode as a thing which depends or inheres in a substance and cannot be clearly conceived apart from it (CSM I 210, 214).

Does Suárez also think that the difference between res and mode concerns dependence? For Suárez, ‘substance’ refers to one of the categories, which tell you what kinds of beings there are. But the distinction between res and mode cross-cuts categorical distinctions. In this sense, a res and a mode are not kinds of beings. Notice how much less weird Descartes’s substance-mode distinction sounds than the res-mode distinction: it’s less weird to say that a mode is something but not a substance than that it is something but not a thing (res). It seems perfectly possible for one thing to depend on another thing without endangering its thinghood. Causal dependence, according to most philosophers, is such a dependence. Of course, metaphysical dependence is more complicated, but at least on its face, Cartesian modes are just kinds of things.

Can we understand Suárezian modes in the same way, so that a mode’s so-called ‘diminished’ being is just dependent being? After all, Suárez characterizes a mode as something that is “intrinsically and essentially required to be always attached to something else.” Looking backward from Descartes, we might be tempted to read this ‘attachment’ as intrinsic and essential dependence, and to characterize a res as an independent being and a mode as a dependent one. But this would be wrong.

As Schmaltz explains, Suárez thinks that dependence (58) and inherence (60-63) are themselves modes, required to relate two res. For example, the dependence of light on the sun is a mode of the light, which attaches it to the sun. Similarly, inherence is a mode of a real accident, which attaches it to its res. In fact, according to Suárez, a res is precisely something that “is either incapable of union with another thing or at least cannot be united except through the mediation of another mode that is naturally distinct from it.” In contrast, a mode doesn’t need anything else to attach it to a res.

“Fine!”, you might reply. “That’s what makes the dependence intrinsic and essential.” Maybe what Suárez calls ‘dependence’ doesn’t apply to the relationship between a res and a mode, but what Descartes calls ‘dependence’ doesn’t involve the mediation of another mode. So their pictures are still pretty similar.

However, Suárez characterizes this ‘attachment’ between a res and a mode not in terms of dependence but in terms of union:

a mode so necessarily includes conjunction with the thing of which it is a mode that it is unable by any power whatsoever to exist apart from that thing. This is a sign that such conjunction is a certain mode of identity. Accordingly there is a lesser distinction between this mode and its subject than there is between two things. [my italics]

The imperfection of a mode is not that it is dependent on a res, essentially or otherwise. It is that it is not quite distinct from its res and so not quite a thing.

Suárez first establishes the theory of distinctions, characterizing them in terms of their distinctionyness. He then uses those to define res and mode. Descartes first defines substance and mode, and then uses that to establish a theory of distinctions. He introduces the distinctions as instructions for truly counting different kinds of things: “Now number, in things themselves, arises from the distinction between them. But distinction can be taken in three ways . . .” (CSM I 213). A distinction is defined in terms of which kinds of things it counts as two.

In a slogan: for Descartes, the modal distinction is a kind of distinction, but for Suárez, it is a kinda-distinction. For Descartes, a mode is a kind of thing (viz., dependent), but for Suárez it is a kinda-thing.

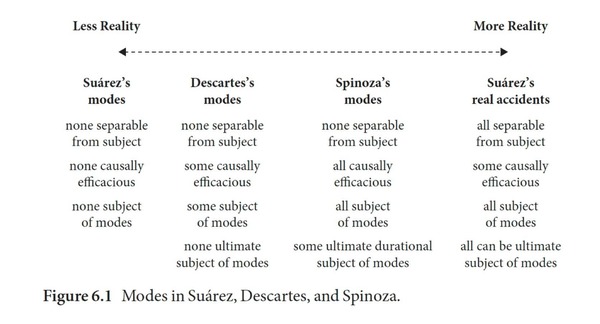

I am not sure to what extent Schmaltz would agree with this analysis. A central argument of Schmaltz’s book is that modes become “more real” from Suárez to Descartes and eventually to Spinoza, as encapsulated by this neat chart (208):

The chart is illuminating. But putting the matter in terms of increasing “reality” obscures what I take to be a transition in kind between Suárez’s view and Spinoza’s and between the problems the theory of modes and the theory of distinctions are aimed at solving.

Schmaltz does describe Descartes’s theory, which Spinoza inherits, as “non-Suárezian” inasmuch as the relationship between substance and mode is one of inherence (229). But he also describes it as a “streamlined Suárezian” one in light of their shared identification of mutual separability, nonmutual separability, and inseparability as marks of the three distinctions. While Schmaltz is very clear that these are only marks of the three distinctions and do not constitute them, this focus de-emphasizes the difference in their projects. For Suárez, God can’t create modes alone because they aren’t really entities, while for Descartes—well, it’s not clear since, as Schmaltz acknowledges, Descartes is voluntarist about even eternal truths.

I am, more generally, a little bit skeptical that Descartes invests nonmutual separability with as much importance as Suárez does. Famously, mutual separability helps Descartes establish a real distinction, but he rarely deploys nonmutual separability, and sometimes even writes that separability (period) entails distinction (period), and describes the modal distinction as a mere distinction of reason. Schmaltz seems to acknowledge that Descartes didn’t have this all tied up. In fact, I left Schmaltz’s discussion of Descartes alongside Suárez and Spinoza with a new sense that Descartes wasn’t really concerned with metaphysics of this sort. With extension, motion, surfaces (as Schmaltz beautifully shows), organic organization, the soul-body union—yes. But the Suárezian structure feels like a retrofit. I wonder if Schmaltz would be OK with that takeaway.

I don’t want to overstate the difference between Suárez and Descartes. Both are clearly struggling with the relationship between entity and dependence, and appeals to degrees of reality are precisely meant to relate the two. Descartes often writes (usually when corresponding with someone steeped in Scholasticism) that modes are not full beings or fully distinct, while Suárez stresses that modes have a certain kind of entity. But their emphases are different in kind, not just in degree.

The difference is crystallized in one particular shared posit, which Schmaltz offers as evidence of Suárez’s influence on Descartes. For both, there are two kinds of modal distinction: one is between a mode and its res (for Suárez) or substance (for Descartes), and the other is between two modes of the same substance. What is going on in the modal distinction of the second kind? Suárez is thinking: we’re counting res, and there are not two res there, so there’s a modal (viz., kinda-) distinction between them. But Descartes is thinking: we’re counting modes, and there are two modes there, so there’s a modal (viz., between modes) distinction between them.

So there is a real difference in how the two think that two modes of one res/substance relate to one another. For Suárez, it is hard to talk about a mode doing anything or entering into any metaphysical relationships directly, without communicating through its res. The more we reify modes, the more natural it seems to talk about the things they do without invoking their relationship to their substance. Schmaltz stresses the distinctions between Suárez and Descartes that reflects this: Descartes allows modes of modes, while Suárez does not; Descartes thinks that modes can be causes, while Suárez does not.

Let’s turn now to Spinoza. Schmaltz argues that Spinoza is even more of a realist about modes than Descartes. This will be surprising if you associate Spinoza with acosmism, but Schmaltz has good reasons for his reading (so do the acosmists; that’s just the way it goes). Like Descartes, Spinoza often speaks of modes as full entities of their own, albeit ones that depend on substance. Sometimes it sounds almost like modes live together happily in their own special realm where they get to act like res. On that reading, it makes sense that modes can do all the things that substances do, like have modes and effects of their own.

I’m more interested in another example of this: composition. Schmaltz argues that Spinoza is committed to “a new metaphysical category” (228): modal parts. Substance is one and indivisible, but composition lives on in the modal realm, where modes join to compose complex modes. An important source of Schmaltz’s reading is a passage from the early Cogitata Metaphysica where Spinoza describes Descartes’s theory of distinctions and then writes:

From these three all composition arises. The first sort of composition is that which comes from two or more substances that have the same attribute (e.g., all composition that arises from two or more bodies) or that have different attributes (e.g., man). The second comes from the union of different modes. The third, finally, does not occur, but is only conceived by reason as if it occurred, so that the thing may be more easily understood.

Schmaltz names the second kind composition from “modal parts”.

Spinoza presents the Cogitata Metaphysica as Descartes’s philosophy, not his own (as Schmaltz admits), so this is quite weak evidence. Schmaltz cites some other evidence, but I confess I’m not entirely sure why he wants to save parts for Spinoza. He argues at some length that Spinoza’s arguments against the divisibility of substance do not preclude modes from having modal parts (230–232), which does not, of course, show that they do. And that argument depends on treating modes as living in that little modal universe, blissfully unconstrained by the God on which they depend. But this is bad! Spinoza doesn’t like it when we treat modes as “abstracted from substance”, as he puts it.

Schmaltz’s claim that the indivisibility of substance does not entail the indivisibility of modes is part of his argument against my own reading of Spinoza (235), on which neither substance nor modes are divisible “by their nature”, or fundamentally. Against a different reading by Ghislain Guigon, Schmaltz writes that Guigon’s argument “seems to assume that if material parts were to compose an infinite whole, then extended substance itself would be composite, contrary to Spinoza’s monism. I suspect a similar assumption underlies [Peterman’s] argument against the reality in Spinoza of divisible spatial quantity” (240). But it does not. What I assume is that the fact that creatures are modes of substance places constraints on their ability to compose in this way. The constraint, basically, is this: modes depend on substance; a composite mode would depend on its parts; and it doesn’t make a lot of sense for modes to be involved in both of these dependence structures. As Yitzhak Melamed put it, “the poor mode becomes the servant of two masters.”

I would add that the argument I make in the paper Schmaltz generously engages is specific to spatial divisibility, as part of an argument that three-dimensional extension isn’t the sort of thing that can be a fundamental feature of bodies. But I have, on the basis of considerations like the above, come to think that modes in general are not divisible and that part and whole do not play an important role in Spinoza’s metaphysics.

This is hard to defend, because there is no single historical conception of composition. But one core part of many such conceptions is that in composition, two fully distinct things become fully one thing. Suárez does not think that modes can compose: they are not two things and cannot become one thing. This is less clear in the case of Descartes. Schmaltz argues that “at least with respect to quantity, there is no room for the notion of a modal part in Descartes’s system. This is clear from his discussion of the ontological status of surfaces” (229). But I don’t think the argument Schmaltz suggests for that is valid: that Descartes does not think that the parts of bodies inhere in them does not entail that he thinks that someone who does think that is guilty of a category mistake. So I’m not sure about Descartes.

What about Spinoza—does he thinks that two modes can become one mode? I think not. I can’t fully defend that here, but here’s an example of a passage that Schmaltz and I read differently. Spinoza writes:

we conceive that water, insofar as [quatenus] it is water, is divided and its parts separated from one another; but not insofar as it is corporeal substance. Again, water, insofar as it is water, is generated and corrupted; but insofar as it is substance, it is neither generated nor corrupted.

This is Schmaltz’s gloss: “It is not water simpliciter that is divisible and mutable, but only water quatenus a mode of extended substance.” But the passage says that “water, insofar as it is water, is divided”—what is that if not water simpliciter? The question is: what is water? I’m not convinced it is a mode, so I don’t think passages like these show that modes are divisible.

I always learn so, so much from Schmaltz’s work, and this book is no exception. He is a careful scholar, an incisive reader, and a generous interlocutor. I highly recommend it!